Table of Contents

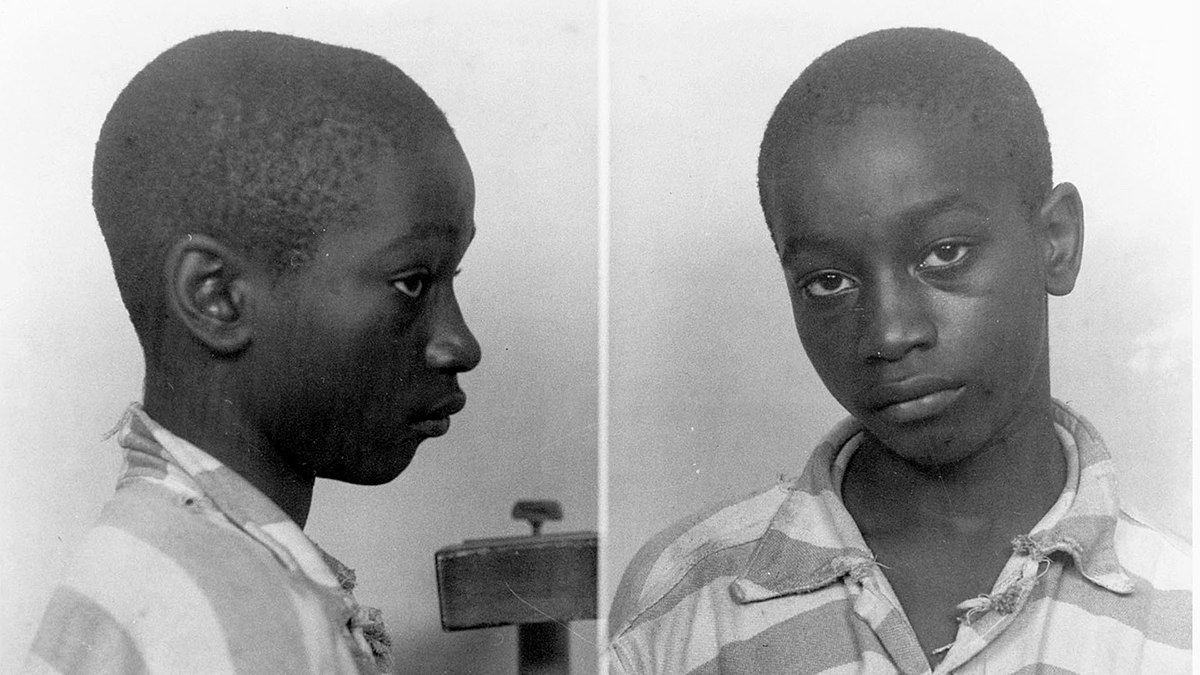

George Stinney Jr., 14, was arrested by police at his home in Alcolu, a town in South Carolina, while his parents were away. His little sister hid in the family chicken coop and watched as George and his older brother Johnny were handcuffed and taken away.

They had previously found the bodies of two white girls. They had been brutally murdered. They had been beaten over the head with a railroad spike and thrown into a ditch filled with water.

George Stinney Jr, 14, was electrocuted in 1944 for murdering two white girls and exonerated 70 years later

“The police were looking for someone to blame, so they used my brother as a scapegoat,” his sister Amie Ruffner told WLTX-TV in 2014.

It was March 1944. American “Aparheid,” the political and social system based on racially based segregation of the population and discriminatory treatment of the black population, was in full force in that southern state.

Three months later, on June 16, 1944, George Stinney was executed. He became the youngest person, at that time, to be an executive.

Seventy years later, in 2014, George Stinney was exonerated of all guilt. This case was for many years one of the flagships of civil rights advocates.

It was an unwarranted case

George Stinney, once at the police station, was interrogated alone, without his parents, without a lawyer. It was still 19 years before the landmark case of Gideon v. Wainwright, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that every person in custody had the right to an attorney.

The Deep South Police claimed that the boy confessed to killing Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8, and that he had been motivated by his intent to have sex with Betty.

With that confession, the trial happened very quickly.

Barely a month later, on April 24. It lasted barely two hours. The jury’s deliberation took 10 minutes. He was sentenced to death by electrocution.

At that time, it was enough to be 14 years old to be criminally responsible. His lawyer decided not to appeal.

It was a trial without evidence of any kind that could well have taken place in the worst times of South African “Apartheid”, thousands of miles away.

The defense counsel called no witnesses. Nor was there any record of the confession. The case has haunted that city ever since.

The executed boy had a cut

George also had an alibi: his younger sister, Amie Ruffner, who in 2014 was 77 years old.

Amie testified before the judge that George that when the crime happened her brother was with her, watching their family’s cow grazing by the railroad tracks.

At that time, the two girls approached them riding their bicycles and asked them where they could find wildflowers. They replied that they didn’t know and went on about their business.

Stinney was accused of murdering the two girls just as they were picking wildflowers.

The boy’s family, after the execution, fled town. His brother, Charles, now 80, said they never went to the Police because they were terrified.

“George’s conviction and execution was something my family believed could happen to any of us in the family. Therefore, we made the decision for the safety of the family to let him be,” Charles Stinney wrote in his affidavit.

Circuit Judge Mullen eventually overturned the conviction with her sentence, in response to the coram nobis brief.

70 years later.

“I can think of no greater injustice than the violation of the constitutional rights that have been proven to me in this case,” he wrote at his sentencing. George Stinney was electrocuted 84 days after the murder of the two girls.

He was just 5 feet 6 inches tall and weighed just 100 pounds. The straps of the electric chair were too big for his small body. The newspapers of the time reported that several books had to be placed in the chair so that he could reach the electrode in his head.

With her sentence, Judge Mullen restored the honor of the executed boy and his family, correcting the 1944 sentence. She could not give them back their brother’s life or take away the suffering they had endured for decades.

But justice was done.